One big beautiful food crisis

Reprinted with permission from the Arizona Agenda, August 8, 2025 article by Nicole Ludden and Hank Stephenson

Arizona is home to the global food bank movement, but federal cuts could strain its limits.

Ground zero for hunger relief

In 1967, John van Hengel opened the nation’s first food bank in Phoenix to fill in gaps that government food assistance didn’t cover.

Nearly 60 years later, federal cuts are threatening St. Mary’s ability to fill the void.

Food banks usually see increased demand during economic downturns. The National Guard was deployed to help food banks cope with rising demand during the onset of COVID-19, and community food programs served millions more than usual during the Great Recession.

But food banks like St. Mary’s can’t replace millions in government aid when the cuts to SNAP, or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, take effect through President Donald Trump’s “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” next year.

In 1967, John van Hengel founded the first food bank at an abandoned bakery at 816 S. Central St. in Phoenix

Last fiscal year, 923,400 Arizonans received SNAP benefits, which give low-income families a monthly allowance to buy food.

The various provisions in the federal budget bill that slash the SNAP program have staggered effective dates, but estimates put the total number of Arizonans at risk of losing at least some food assistance at 73,000.

That’s based on the new work requirement for SNAP recipients; the actual hit could be much larger.

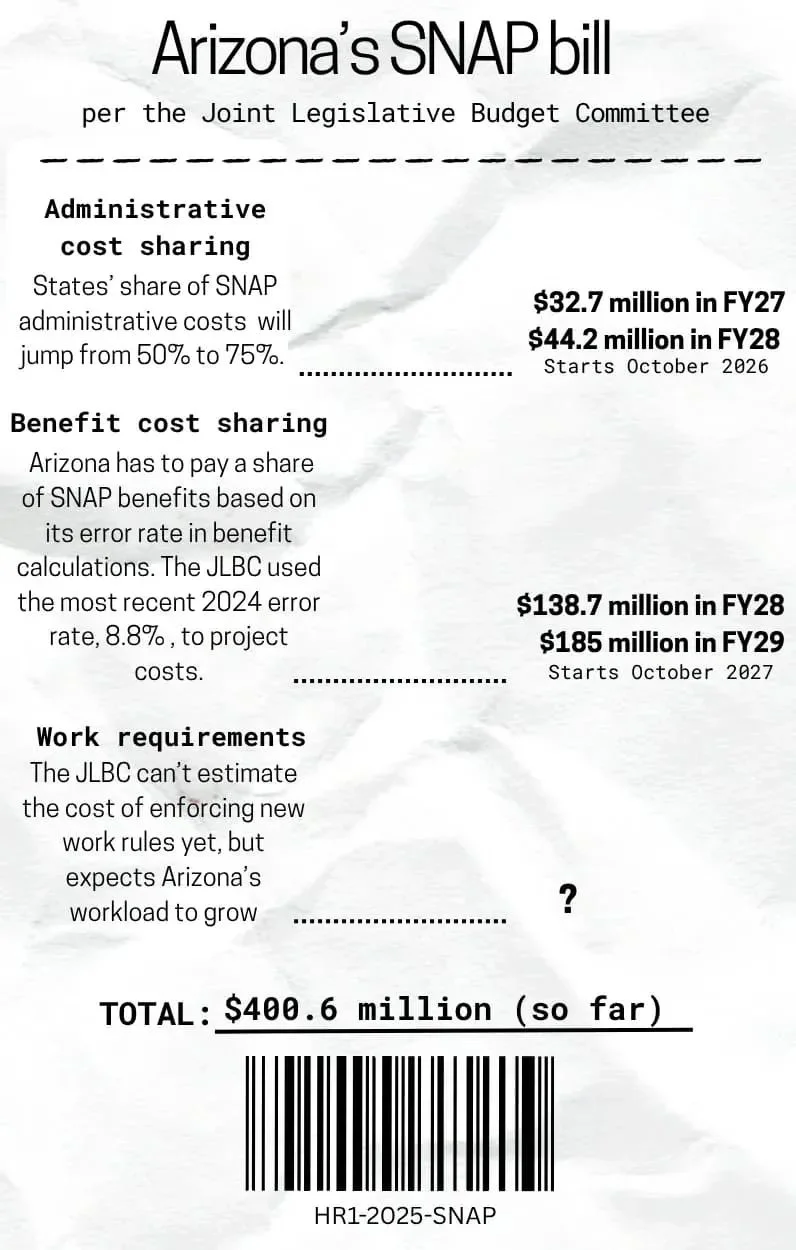

Deeper cuts could come as Arizona has to start footing 25% more in SNAP administrative costs and 10% of the benefits themselves, as the new rules state. The Legislature’s financial experts estimate the changes will cost $400 million through fiscal year 2029 — assuming lawmakers want to keep benefits at their current levels.

But Arizona, the birthplace of the food banking network, surely has enough community-based food aid to make up the shortfall, right?

Wrong, according to the leaders of two of the state’s largest food banks.

St. Mary’s started in an abandoned downtown Phoenix bakery, and Van Hengel went on to build the global model for food banks. Now, St. Mary’s covers a 67,000 square mile service area across Arizona and distributes about 125 million pounds of food a year. Last fiscal year, it recorded 2.2 million visits.

But the expected surge in demand from the incoming SNAP cuts could overwhelm Arizona’s food bank system, according to St. Mary’s CEO Milt Liu. Even before cuts set in, demand at St. Mary’s Surprise location was up 46% last week compared to the same week last year.

“The value of SNAP far exceeds what food banks provide. The numbers would say that there's no way that food banks can make up for all the lost dollars of SNAP,” Liu said. “We have never turned anyone away in our network, and our goal is to continue to provide.”

Christopher Bodnar, the director of agency network at United Food Bank, has the same concern. With 130 partners serving from Tempe to the New Mexico border, United Food Bank provided about 40 million of the about 195 million4 meals distributed by Arizona’s regional food banks last year. By comparison, SNAP covers nearly 1 billion meals annually in Arizona, per Bodnar.

“There's no way we could cover that gap,” he said.

A double whammy

On a Friday morning in Surprise, two lines formed outside St. Mary’s Food Bank. On the west side of the warehouse, volunteers distributed prepackaged emergency food boxes.

More people were waiting along the east end, where visitors enter a grocery-style market that the food bank opened last year. Volunteers guide them through with a cart, and bag their food with plastic bags. It’s a small act of dignity for those who continuously see it stripped away.

None of the seven people we spoke to at St. Mary’s said they receive SNAP benefits.

Many rely on Social Security and Medicaid, but don’t qualify for food assistance. And while they were all there for the same reason, they had different views on government benefits.

Amanda told us she and her husband both work, but turned to the food bank after moving from Colorado with nothing. She doesn’t follow politics, but believes people should work for the food aid they receive.

Rosa, meanwhile, thinks the incoming federal cuts are a “disgrace.” She used to rely on her husband’s income, but paying the bills has been difficult since he was diagnosed with cancer. She’s worried the incoming cuts to Medicaid will keep her from affording his medicine.

To be clear, if St. Mary’s is overwhelmed by people losing federal assistance, it won’t shut down overnight. But there will be less food to serve more people, and a slow erosion from there.

Earlier this year, the food bank was short a million pounds of food after the U.S. Department of Agriculture axed a program that lets food banks buy from local farmers.

It’s not a huge dent compared to the estimated 125 million pounds of food St. Mary’s distributes each year, but it still strains a supply-and-demand equation that’s already been destabilized by COVID-era price inflation.

“It's kind of a double whammy. We had food reduced, and what's happened with this bill is that we're likely to see more demand,” Liu said.

The new poor

If you think the idea that SNAP cuts could overwhelm food banks is dramatic, some history for you …

The United States’ current food assistance policies stem from the Great Depression, when people filed into breadlines and soup kitchens run by private charities and churches as farmers destroyed their surplus food stock to raise food prices.

The food stamp program evolved from the government’s decision to distribute surplus food to the hungry. Since then, both Republicans and Democrats have proposed food benefit cuts, but Ronald Reagan was the first to make official cutbacks in the early 1980s.

After those cuts, the U.S. Government Accountability Office examined how a poor economy and reductions in federal food aid were affecting Americans. The office found that not only were more Americans seeking food assistance, but the kinds of people seeking help changed.

“No longer are food centers serving only their traditional clientele of the chronically poor, derelicts, alcoholics, and mentally ill persons who typically live on the streets and who most probably will be in need no matter what happens in the economy,” the authors wrote in the 1983 report.

“Today, many organizations report that a mounting number of ‘new poor’ are contributing to the increasing numbers seeking assistance at many emergency shelters and food centers … They now find themselves without work, with unemployment benefits and savings accounts exhausted, and with diminishing hopes of being able to continue to meet their mortgage, automobile, and other payments which they committed themselves to when times were better.”

Page 20 of the U.S. Government Accountability Office’s June 1983 report notes the success of the food bank model that St. Mary’s started.

Over time, the harshest Reagan-era cuts were rolled back through congressional negotiations. But they provided an important lesson on the fragile balance between public and private food aid.

"[The food bank movement] is not — and never will be — the solution to our hunger problem,” the 1983 report quotes from a food bank executive. “Foodbanks could never replace any of the federal programs that help feed people — they are only one link in the vital network of private and governmental programs to feed the poor."

Since the Reagan era, the argument against food stamps has largely remained the same: They create dependence on government aid that discourages people from working.

Shortly after Trump cemented social program cuts into law, Republican Sen. John Kavanagh called the resulting outcry “Trump Derangement Syndrome,” and said, “the only people who will not get Medicaid or SNAP benefits are able-bodied adults."

It’s a little more complicated than that.

In general, those who make 130% or less of the federal poverty level qualify for SNAP — that’s about $40,000 a year for a family of four. If they don’t have kids or a disability that keeps them from working, adult SNAP recipients can only get 3 months of benefits within 3 years. And they have to prove they work or attend work training at least 20 hours a week.

Also, the application process is full of administrative hurdles. In 2015, researchers found 40% of people who were eligible for SNAP didn’t apply because of the paperwork.

The federal changes expand the work requirements to those ages 55 through 64, parents whose youngest child is 14 or older, veterans, foster youth and homeless people.

Those without lawful permanent resident status, like refugees and asylees, will completely lose their SNAP benefits.

The Joint Legislative Budget Committee, the legislature’s financial experts, estimated federal SNAP cost-shifts to states will cost Arizona $215.6 million through fiscal year 2028. They have yet to publish numbers for how much more the state will have to pay for implementing new work requirements.

States are waiting for federal guidance before implementing the new eligibility rules. But regardless of eligibility, Arizona’s entire SNAP program is at risk if the state doesn’t come up with hundreds of millions to cover costs the federal government says it no longer will.

Gov. Katie Hobbs previously said Arizona doesn’t have enough money to cover the difference of all the federal cuts. The latest messaging is that her office is going through the changes “with a fine-toothed comb to understand the full implications of this legislation and how to best protect Arizonans.”

But the first cost-sharing provision starts in the fall of 2026, so Arizona’s lawmakers have to figure it out next year. And the Democratic governor and Republican legislative majority have found themselves in partisan gridlock over much less.

Until then, maybe there’s something to be learned from Van Hengel, the father of the food bank.

In a 1992 Los Angeles Times profile, Van Hengel recalled receiving a telegram from his old sales job asking him to come back. He declined — Van Hengel had already started picking citrus to deliver to local charities, a practice that morphed into the modern-day global food bank model.

“I had freedom, and people were becoming more important than money,” he said.